Introduction

In the month of Ordibehesht 1403 (20 April 2024- 20 May 2024), widespread executions were carried out in Iran, which are significant due to the circumstances of their implementation and their impact on society and human rights. This report strives to provide a clear picture of the execution situation during this month by precisely examining the events and existing evidence. Since access to accurate and unbiased information in Iran faces numerous challenges, this report endeavors to use credible sources and reports from human rights organizations such as HRANA, Hengaw, Kurdpa, Halvash and the Iranian news agencies not only to obtain statistics but also to explore the reasons and consequences of these executions.

Specifically, this report attempts to provide a deeper analysis and detailed description of executions related to drug offenses, murder, and political charges. It also considers the impact of these executions on the grieving families and the community and addresses how these events are covered in the media both inside and outside the country. This report is prepared with the aim of increasing awareness in the international community and creating political and legal grounds for exerting more pressure on the government of Iran to adhere to human rights and international laws.

As these issues are not confined to one country but are part of global human rights issues, attention and follow-up by the international community can be effective. Ultimately, this report is presented to you with the hope of initiating change and improving legal and human rights standards in Iran.

Report Content

Data indicates that on the 20th, 22nd, and 26th of April, and the 3rd, 4th, 10th, 13th, and 20th of May, no executions were reported. However, the highest number of executions occurred on the 21st of April, with 14 people executed on that day.

Geographic Distribution

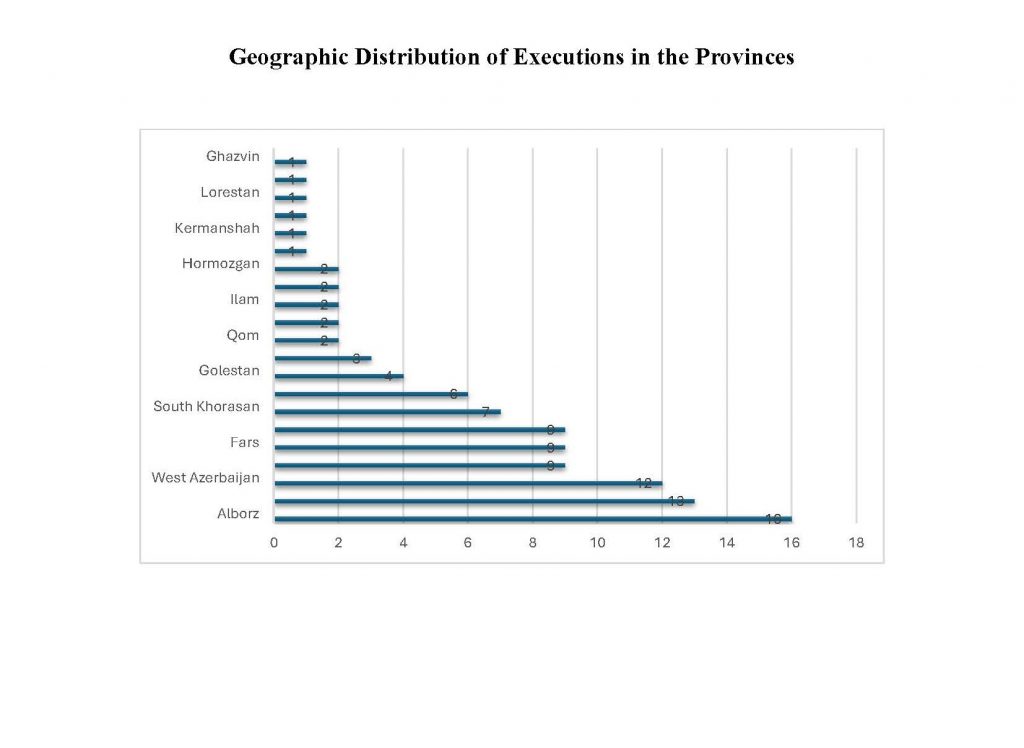

Executions during this period took place across 21 provinces of Iran and in a total of 31 prisons located in various cities throughout the country. Alborz province, with a total of 16 executions (approximately 15.38%) carried out in three prisons—Ghezel Hesar, Karaj—had the highest number of executions, followed by Kerman with a total of 13 executions (12.5%) in three prisons located in Kerman, Kahnouj, and Bam, ranking second. Following these two provinces, West Azerbaijan ranks third with a total of 12 executions (11.53%) in three prisons in Urmia, Salmas, and Miandoab.

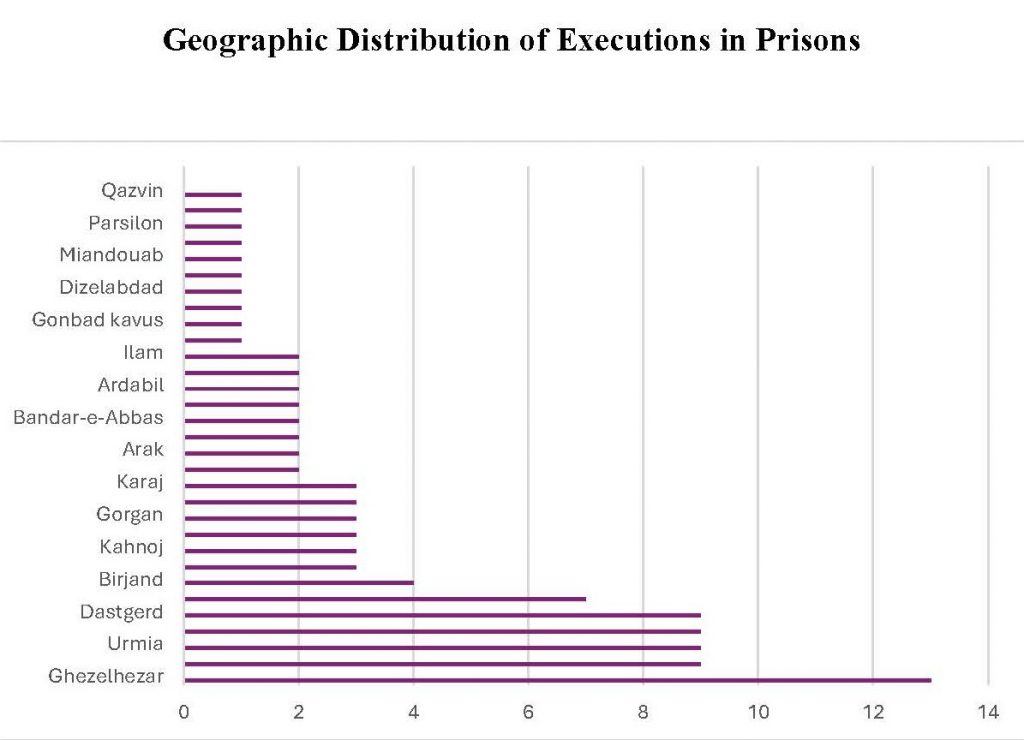

The distribution of executions based on prisons shows that Ghezel Hesar Prison, with a total of 13 executions, had the highest number of victims. Following this are the prisons of Adel Abad in Shiraz, Urmia, Tabriz, and Dastgerd in Isfahan, each with 9 executions. Kerman Prison ranks third with a total of 7 executions.

Among the executed, the identity of 9 individuals remains unknown, with six of them being executed on drug-related charges and the rest for murder. Six of the victims were Afghan nationals, and six were women. According to available data, the age range of those executed was between 22 to 53 years old.

One of the victims, Ramin Saadat Zamani, was accused of murder during a street fight at the age of seventeen. Despite repeatedly asserting his innocence, he was hanged in Miandoab Prison on the 11th of May. At the time of his execution, he was 22 years old.

Reasons for Executions

The data shows that executions were carried out for three different reasons:

Drug-related crimes: A total of 67 executions were carried out in connection with drug-related crimes. These cases do not only reflect the government’s stringent policies against drug trafficking and the expansion of drug trafficking and consumption in the region. Most of those who have been executed are from the most vulnerable and disadvantaged strata of society. Even cases involving the transportation of relatively small quantities of drugs have led to the death penalty.

Murder: Another crime leading to capital punishment this month is murder, resulting in the execution of 35 individuals. Executions arising from murder cases often follow private disputes and acts of personal revenge. In some instances, the laws of retribution (Qisas) allow the victims’ families to request the execution of the perpetrator, which indicates an adherence to Sharia laws within the Iranian judicial system.

Political and security crimes: Iran has also witnessed executions based on political and security charges this month. Two of the victims, Khosrow Besharat and Anwar Khedri, were political prisoners who were executed on the 1st and 15th of May, respectively, after fourteen years of imprisonment. Trials in such cases typically lack transparency and justice, often with no access to appropriate legal defense or a fair trial.

Human Rights Violations: Execution of Vulnerable Individuals and Mass Executions

Although the execution of individuals in vulnerable groups and mass executions in Iran is not a new phenomenon, investigations indicate that this tragedy has been repeated in the designated period.

Execution of Vulnerable Individuals

Investigations show that some of the victims not only belonged to marginalized sections of society but were also practically vulnerable and lacked rehabilitative and caregiving support. Among those executed was 53-year-old Parvin Moosavi, who was suffering from cancer; she was executed on the 18th of May in Urmia Prison in a case related to the trafficking and sale of drugs.

Rashed Baluchi, a 35-year-old, was executed on the 28th of April in Bandar Abbas Prison for murder, while according to Hengaw reports, he had a mental illness and possessed a medical red card.

The Tragedy of a Mother and the Impact of Economic and Social Problems:

Mrs. Razieh, a mother who was executed on the 16th of May in Vakilabad Prison for killing her two children, is an example of how severe economic and social challenges can lead to human tragedies. After separating from her addicted husband, Razieh took on the full responsibility of providing for and caring for her two children, aged four and eight. Despite her continuous efforts to meet the basic needs of her family, the financial and social pressures gradually drove her to complete despair. Faced with homelessness and severe poverty, Razieh found herself in a situation where she felt there was no way out. Unable to find work as a caregiver for her two children and also deprived of sufficient support from social systems and local charities, she ultimately took the desperate action of killing her own children. This act, driven by despair and hopelessness, points to the depth of the economic and social crises.

State-controlled media extensively covered her execution, portraying her as a heartless and cruel mother. This portrayal, however, casts a shadow over the attention to the depth of the social crisis and its role in this tragedy. Such media representation not only contributes to overlooking the root causes of the problems that lead to such events but also highlights the lack of necessary social and psychological support to assist individuals in similar circumstances.

Mass Execution: Case of Joint Murder in a Street Fight

One of the controversial and concerning cases regarding executions this month involves the mass execution of individuals involved in a joint murder during a street fight. In this particular case, six people were sentenced to death, and five of them were executed on the 12th of May. The sixth individual, Qasem Salehi, managed to avoid the death penalty by paying a Diya (blood money) amounting to 5 billion tomans, thereby gaining the forgiveness of the victim’s family.

This case exemplifies how the Iranian judicial system collectively sentences individuals involved in a crime to execution, regardless of each individual’s role and level of involvement. Mass executions not only address issues related to individual justice but also highlight significant differences in the application of the law. The issue of paying Diya and differences in the fate of the accused also points to deeper issues of economic justice and financial discrimination, indicating that individuals with better financial access can achieve more favorable judicial outcomes.

Impact of Executions on the Families of the Victims

Based on the published details about the victims executed this month, a portion of the information pertains to those who were married and had children. Of the 104 victims executed in Ordibehesht (from 20 April to 20 May), it has been confirmed that 29 were married, and out of this number, 26 had children. Considering the age of the executed victims this month, it can be claimed that a greater number were married, but due to the lack of sufficient information, it is difficult to make a definitive statement about the exact number.

Although the ages and genders of these children are not clearly specified, it can be generally stated that at least 39 children and young people have lost a primary caregiver (either father or mother) due to the executions. The age range of these caregivers is between 25 to 53 years, with each having at least one and at most nine children. Twenty-six of these caregivers were executed in connection with drug-related crimes.

Challenges in Reporting and Access to Information

One of the biggest challenges in reporting executions in Iran is the limited and difficult access to accurate and reliable information. Journalists and human rights activists often face obstacles such as government censorship, legal restrictions, and security risks in gathering and publishing information. These issues, especially in cases of executions carried out without prior notification or in media silence, become more apparent. Moreover, restrictions on access to prisons and courts, as well as the lack of transparency in judicial proceedings, create additional challenges for reporting. These conditions sometimes result in published reports being incomplete or biased, negatively impacting efforts to present an accurate and comprehensive picture of the state of executions in Iran.

To provide a correct depiction of the dire situation of executions in Iran, it is the responsibility of the survivors, friends, and citizens whose loved ones and children have been victims of executions. We are always ready to be your voice.