1. Introduction

In the month of Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025), the Islamic Republic of Iran continued implementing death sentences at an alarming and unprecedented rate. According to the data compiled in this report, at least 70 individuals were executed in prisons across the country during this period. This number reflects an approximately 2.8-fold increase compared to the same month in the previous year, when 25 executions were recorded, highlighting a disturbing acceleration in the use of this irreversible and brutal punishment.

The aim of this report is to document the executions with precision, shed light on the judicial processes involved, and inform the public, international bodies, and human rights defenders. This effort serves the broader purpose of protecting the right to life, preserving historical memory, and resisting the normalization of judicial violence in Iran.

The compilation of this report has faced significant challenges, including lack of transparency from official institutions, widespread media censorship, pressure and threats against the families of those executed, and serious security risks for local sources. Despite these obstacles, we firmly believe that accurate documentation and public dissemination of this data is a crucial step toward justice, raising public awareness, and demanding accountability from the authorities.

2. Report content

This section provides an analysis and detailed account of the executions carried out during the month of Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025). The compiled data includes the geographical distribution of executions, the nature of the charges brought against the defendants, the nationality and gender of those executed, and the judicial processes observed in their cases. In addition, selected instances of legal ambiguities and violations of fair trial standards are examined.

This report aims to present a comprehensive and well-documented picture of the widespread wave of executions during this period. It seeks to identify and document the deeply concerning human rights violations committed by the Islamic Republic of Iran, based on verified and credible data.

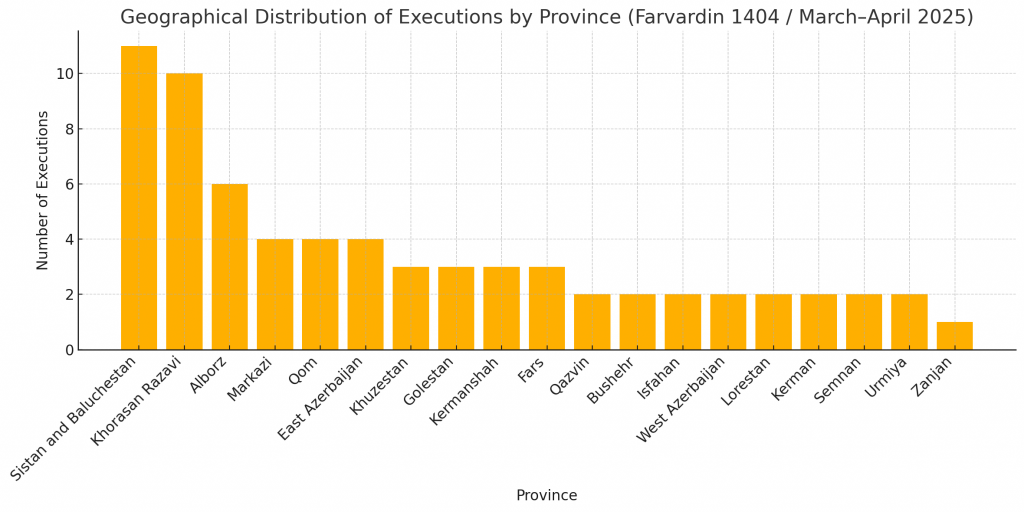

2.1. Geographic Distribution of Executions by Province

The executions carried out during the month of Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025) spanned a wide range of provinces across Iran, taking place in a total of 20 provinces. However, the concentration of executions in certain regions warrants particular attention and analysis.

The province of Sistan and Baluchestan, with 11 recorded executions, had the highest number. It was followed by Khorasan Razavi with 10 executions, and Alborz with 6. Together, these three provinces account for approximately 40 percent of all executions reported during this month.

The geographic distribution of executions reveals that many of these sentences were carried out in marginalized areas or in regions with a high concentration of public and security prisons. For example, Sistan and Baluchestan, a province with a predominantly Baloch and Sunni population, has consistently reported a high rate of executions, especially in cases involving charges such as drug-related offenses and moharebeh (enmity against God).

Other provinces—including Markazi, Qom, Khuzestan, East Azerbaijan, Kermanshah, Golestan, Hormozgan, and Fars—each recorded between 2 and 4 executions during this period. The spread of these numbers illustrates that the death penalty continues to be widely used as a tool of intimidation and repression throughout the country, though it is implemented more intensely in certain areas.

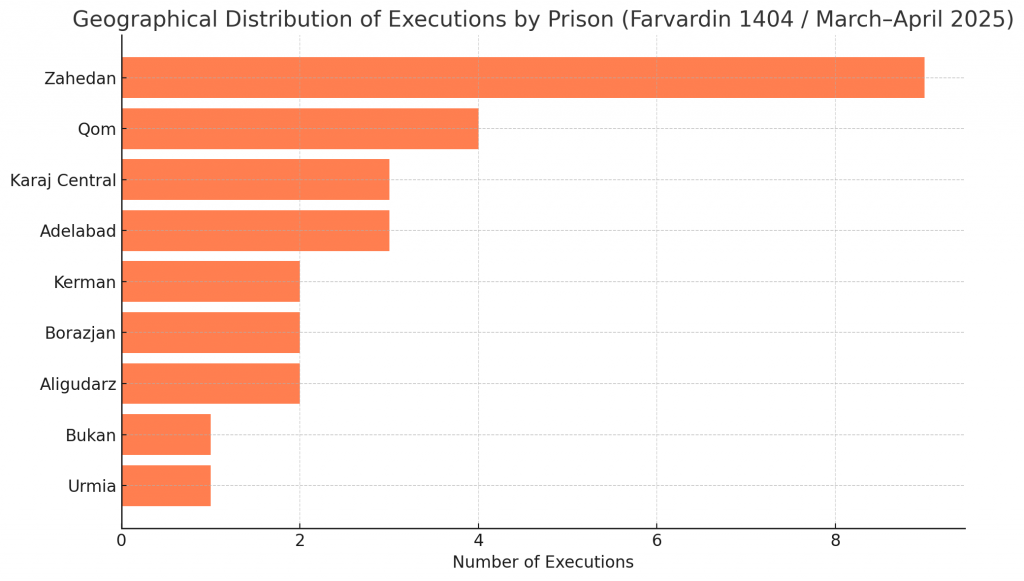

2.2. Geographical Distribution of Executions by Prison

An examination of the locations where executions were carried out in Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025) reveals that the death penalty was implemented in at least 25 different prisons across Iran. Among these, certain prisons accounted for a significantly higher number of executions compared to others.

Zahedan Prison, with at least 9 executions, topped the list. It was followed by Vakilabad Prison in Mashhad, with 8 executions, making it the second most frequent site for carrying out this punishment. Together, these two prisons were responsible for approximately 24 percent of all executions reported in Farvardin, underscoring their central role in the implementation of death sentences.

Arak, Qom, and Tabriz prisons also reported 4 executions each, placing them among the next most active facilities.

Executions were also carried out in lesser-known or smaller facilities such as Gonabad, Choubindar (Qazvin), Aligudarz, Borazjan, Shahrud, and others—highlighting the nationwide spread of executions, even in remote or lower-capacity detention centers.

2.3. Demographic Analysis of Executions

An examination of the demographic characteristics of those executed in Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025) reveals the scope and diversity of individuals affected by capital punishment. The collected data indicates the following:

Of the 70 individuals executed, 69 were men and 1 was a woman. Additionally, at least 3 of those executed were Afghan nationals, highlighting the continued execution of migrants and individuals lacking valid identification documents in Iran—groups that are often subject to legal and judicial discrimination.

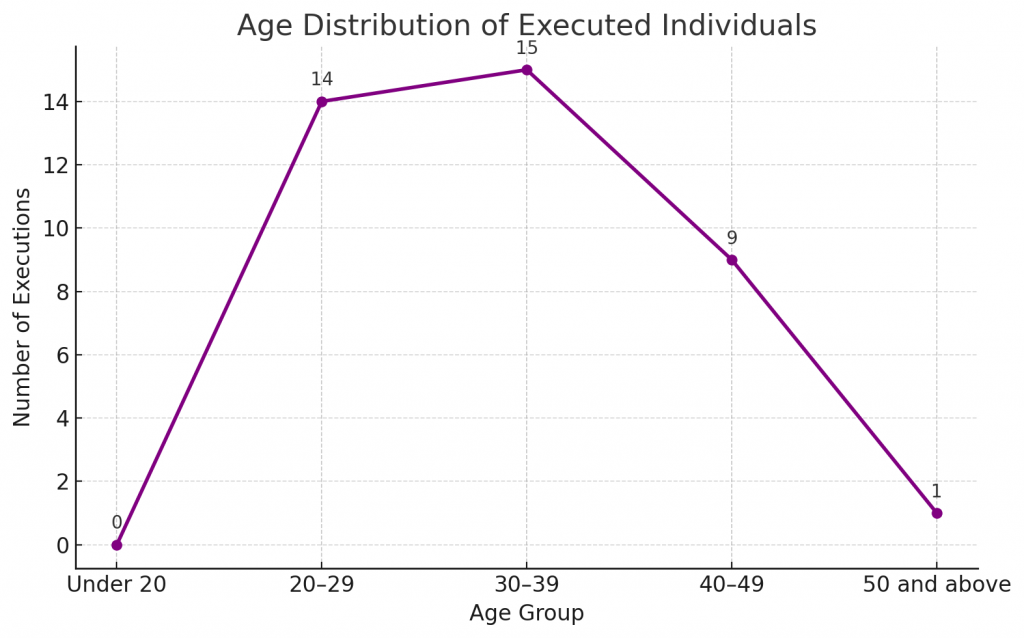

Age information was available for 39 individuals. According to the data, the youngest person executed was 22 years old, while the oldest was 62. The majority of executions occurred within the 20 to 39 age range (29 individuals in total), which represents a stage of life when many are building their careers, families, and social identities.

The fact that only one person over the age of 50 was executed further suggests that the death penalty in Iran is predominantly enforced against younger populations—an issue that raises serious concerns from both a human rights and social psychology perspective.

3. Charges Brought Against Executed Individuals

Among the 70 executions recorded in Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025), the charges can be broadly categorized into three main groups:

- Murder charges: 35 cases

- Drug-related offenses: 29 cases

- Political or security-related charges: 6 cases

More than half of the executions (50%) were related to murder cases. In many of these, serious concerns were raised about the lack of transparency in the judicial process, denial of access to legal representation during interrogation, and the use of forced confessions. Given the irreversible nature of the death penalty, such procedural flaws significantly deepen the concern over its use.

Executions for drug-related offenses continue to account for a large portion of the statistics. The ongoing application of the death penalty as a tool to combat drug crimes, despite its proven inefficacy in controlling the phenomenon, further underscores the failure of the Islamic Republic’s criminal justice policies.

On the other hand, the execution of six individuals on political or security-related charges, including moharebeh (enmity against God) and baghi (armed rebellion), is a serious warning sign of the regime’s increasing use of the death penalty to suppress dissent and opposition. The use of capital punishment against political, ethnic, or religious activists is a blatant violation of human rights and freedom of expression in the country.

3.1. Reopening a Case

Hamid Hosseinnezhad Heydaranlou

Hamid Hosseinnezhad Heydaranlou, a Kurdish citizen from Chaldoran and father of three children, was arrested by security forces of the Islamic Republic on April 12, 2023 (24 Farvardin 1402). He was charged with baghi (armed rebellion) due to alleged membership in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and involvement in an armed clash in 2017 that resulted in the death of eight Iranian border guards.

However, both his family and lawyer maintained that Hamid was in Turkey with his family at the time of the incident, and presented documentation including passport stamps and border records to prove it. Despite this evidence, the Revolutionary Court of Urmia issued a death sentence solely based on the judge’s personal “knowledge” (elm-e-qazi) and without sufficient supporting documentation.

Hamid was held in solitary confinement for over eleven months and subjected to psychological and physical torture in order to extract forced confessions. In the days leading up to his execution, his family—including his ten-year-old daughter—made significant efforts to draw attention from public opinion and human rights organizations, but their appeals were unsuccessful.

His execution was carried out in secret at dawn on Monday, April 21, 2025 (31 Farvardin1404), without prior notice to his family or legal counsel. Authorities refused to hand over his body to his relatives and did not permit a funeral or mourning ceremony.

This case stands as a clear example of human rights violations, the denial of fair trial guarantees, and the use of the death penalty as a tool of political repression in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Ahmad Yavari

Ahmad Yavari, a 40-year-old prisoner from Gorgan, was executed on April 16, 2025 (28 Farvardin 1404) in Gorgan Central Prison on charges of “murder.” He had been arrested about two years earlier in connection with a homicide case and was sentenced to qesas-e-nafs (retributive execution).

According to reports from Iran Human Rights, Ahmad Yavari was married and the father of two sons. The human rights outlet HRANA reported that although the victim’s family had granted their consent and expressed willingness to forgive, his execution was nonetheless carried out suddenly and without prior notice. The lack of official communication with his family or the media highlighted, once again, the absence of transparency and violation of due process that frequently characterize death penalty cases in Iran.

This case also draws attention to a major structural flaw in Iran’s legal system regarding murder cases: the lack of categorization or grading of homicide. In most legal systems around the world, murder is classified based on intent, circumstances, and severity. However, in the Islamic Republic of Iran, all forms of premeditated murder—regardless of context—can result in a death sentence.

Furthermore, Ahmad Yavari’s execution illustrates how qesas (retribution) in practice functions not solely as a personal right for victims’ families, but rather as a state-controlled mechanism that sustains the machinery of judicial violence—even in cases where the plaintiffs have expressed willingness to forgive.

4. Marital Status and Number of Children

One of the lesser-addressed aspects of execution reporting is the direct impact of this punishment on the families of those executed. According to available data from Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025), 9 of the executed individuals were married, while the marital status of the others was not reported. Additionally, reports indicate that 11 of them had between 1 and 10 children—all of whom lost their fathers to execution.

Although this data is limited, it clearly demonstrates that many of those executed were heads of households or individuals with significant family responsibilities. The impact of execution on spouses, children, and surviving family members is often overlooked, even though the psychological, economic, and social consequences can last for years—fueling cycles of poverty, trauma, and instability.

The lack of detailed information on the family status of the remaining individuals also highlights the opacity of the judicial system and the limited resources available for proper documentation. Nonetheless, even these partial findings illustrate a broader reality: in many cases, the death penalty is not merely a punishment for an individual—it is a punishment inflicted upon an entire family.

5. Conclusion

This report was prepared with the goal of documenting the executions carried out in Farvardin 1404 (March–April 2025)—a month during which at least 70 individuals were executed in prisons across Iran. Compared to the same month last year, when 25 executions were recorded, this figure represents an alarming 2.8-fold increase.

The case studies presented in this report—at least two of which are described in detail—once again expose the opaque, politicized, and often hasty nature of the judicial system in the Islamic Republic.

The death penalty continues to be used as a tool of control, intimidation, and repression—a tool that not only violates fundamental human rights, but also proves ineffective in preventing crime from a social perspective.

Despite the many challenges involved in producing such reports—including informational, security, and media-related obstacles—this work remains an essential act of truth-telling, advocacy, and pressure toward the abolition of this inhumane punishment.