1. Introduction

In Ordibehesht 1404, the number of executions in Iran rose dramatically, reaching the alarming figure of 139 people. In comparison, the same period last year (Ordibehesht 1403) saw 107 executions, representing an increase of approximately 29.9 percent. Even more alarming is the steep rise compared to Farvardin 1404 (the previous month), during which 77 executions were recorded. The figure for Ordibehesht therefore reflects a surge of about 80.5 percent in the span of just one month.

This upward trend is a serious warning sign—not only in terms of the sheer number of executions but also the accelerated pace at which death sentences are being carried out. It signals a significant and growing violation of human rights in Iran, particularly the fundamental right to life.

At the same time, public outcry over this new wave of executions has intensified. Families of prisoners, civil society activists, and human rights organizations—both inside and outside Iran—have widely expressed concern over this escalating trend.

This report is based on data collected from reliable sources, including human rights organizations, domestic news agencies, and field reports. It is published by the Iranian Association Against Executions. The purpose of this report is to provide an independent and accurate documentation of the execution trends in Iran, raise public awareness, and press for accountability from the authorities responsible for the systemic violation of the right to life.

It should be emphasized that preparing such a report comes with numerous challenges and limitations, including media censorship, lack of transparency from judicial and security institutions, and the security risks faced by sources of information. Despite these obstacles, the report’s authors have made every effort to compile the most accurate and comprehensive picture possible using diverse and credible sources.

Given the secretive nature of many executions, it is possible that new information will come to light in the coming months, which may lead to updates in the statistics and details presented in this report.

2. Report Content

This section presents an analysis and detailed breakdown of the executions carried out in Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025). The compiled data includes information on the geographical distribution of executions, the types of charges brought against the individuals, their nationalities, gender, and judicial patterns observed in their cases.

Additionally, the report highlights specific instances of legal ambiguities and violations of fair trial standards, which are examined on a case-by-case basis.

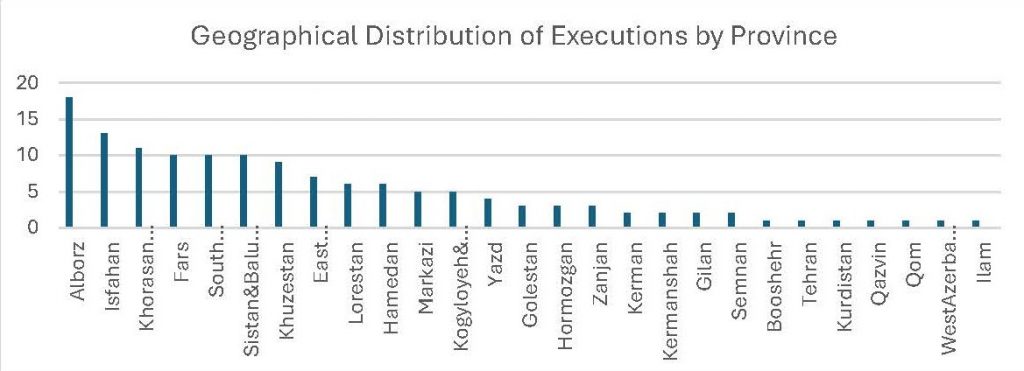

2.1.Geographical Distribution of Executions

In Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025), death sentences were carried out across 27 provinces in Iran, reflecting the national scope of this human rights crisis. A review of the geographical distribution reveals that certain provinces played a disproportionately significant role in the implementation of executions.

Alborz Province recorded the highest number, with 18 executions, accounting for approximately 13

percent of all confirmed executions in this month. This figure cements Alborz’s position as the primary center for carrying out death sentences during this period. Following Alborz, Isfahan Province reported 13 executions, and Khorasan Razavi came next with 11. Fars, South Khorasan, and Sistan &Baluchestan each recorded 10 executions, placing them among the top provinces with the highest number of executions.

This geographic concentration may reflect harsher security and judicial practices in certain regions, or the presence of larger and more active prison facilities capable of processing and carrying out executions more frequently. In provinces such as Alborz, which houses major prisons like Ghezel Hesar, the high volume of executions may also indicate a more centralized and systematic approach to enforcement.

Furthermore, the role of Revolutionary Courts in swiftly issuing and executing sentences—often without adequate guarantees of a fair trial—is considered a major factor behind the elevated execution rates in these regions, particularly where security forces exert significant influence over judicial processes.

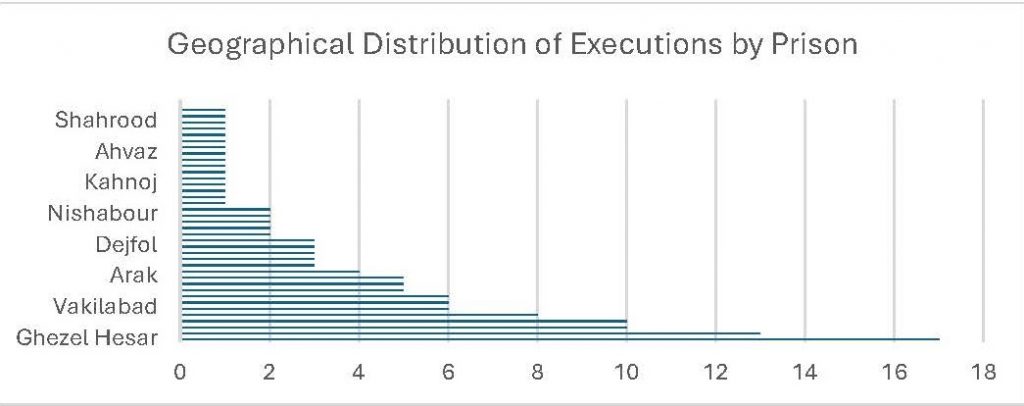

2.2.Geographical Distribution of Executions by Prison

An analysis of where executions were carried out in Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025) shows that death sentences were implemented in a wide range of prisons across the country. Available data indicates that executions were conducted in more than 38 different prisons, underscoring the nationwide scale and geographic spread of this practice.

At the top of the list is Ghezel Hesar Prison, located in Alborz Province, which alone accounted for 17 executions—the highest number among all prisons in the country. Ghezel Hesar has also consistently remained one of the main centers for carrying out executions in recent years, playing a prominent and ongoing role in the Islamic Republic’s punitive and security policies.

In second place is Dastgerd Prison in Isfahan, with 13 executions, highlighting the high concentration of capital punishment carried out at this major central facility.

Birjand Prison and Adelabad Prison in Shiraz follow, each with 10 executions, making South Khorasan and Fars Provinces among those with the highest execution rates in this reporting period.

Zahedan Prison, with 8 executions, also stands out in this ranking and points to the disproportionate pressure on peripheral and ethnic minority regions, particularly in Sistan and Baluchestan Province.

The high concentration of executions in certain prisons may be attributed to factors such as the active presence of Revolutionary Courts, easier access for security agencies, larger prison capacities, and the lack of independent oversight over judicial procedures.

Furthermore, the data shows that executions are not limited to major urban centers or well-known prisons. Death sentences were also carried out in smaller facilities such as Miandoab, Ilam, Gonabad, Kahnooj, and Sabzevar, indicating the systematic and widespread nature of capital punishment across the entire country.

2.3. Demographic Analysis of Executions

An examination of the demographic characteristics of those executed in Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025) provides insight into the range and diversity of the victims of capital punishment in Iran. The collected data reveals the following:

Out of a total of 139 individuals executed, 135 were men and 4 were women. Additionally, at least 5 of the executed individuals were Afghan nationals. This underscores the continuing trend of executing migrants and individuals without valid identity documents in Iran—populations that are often subject to legal and judicial discrimination.

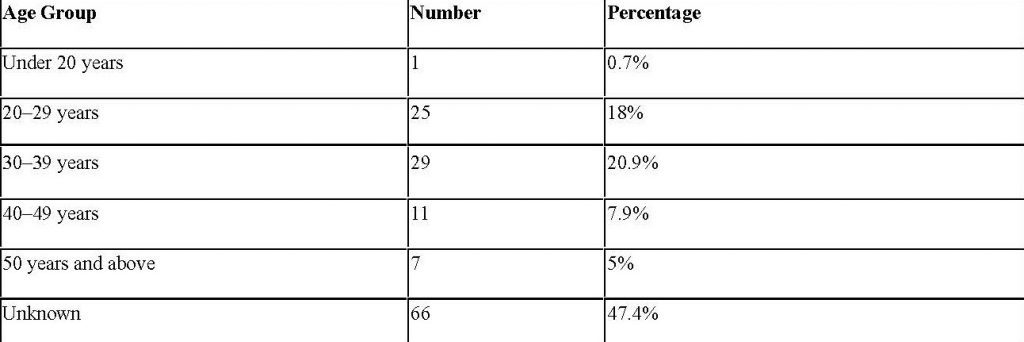

According to available data, the age distribution of those executed is as follows:

Nearly half of those executed were aged between 20 and 39, a demographic that in most societies is considered the productive and active segment of the population. This trend may reflect a judicial system that places disproportionate punitive pressure on the country’s youth.

Furthermore, the presence of two child offenders among those executed constitutes a clear violation of Iran’s international obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Iran is a signatory.

Execution of Two Child Offenders

- Mohammad Reza Sabzi was executed on 23 Ordibehesht in Malayer Prison.

- Hadi Soleimani was executed on 24 Ordibehesht in Adelabad Prison in Shiraz.

According to human rights organizations, both individuals were sentenced to death for murder committed at the age of 16. Mohammad Reza was 20 years old at the time of execution, and Hadi was 18 years old, meaning he was still legally a minor under international standards.

3. Charges Leading to Execution

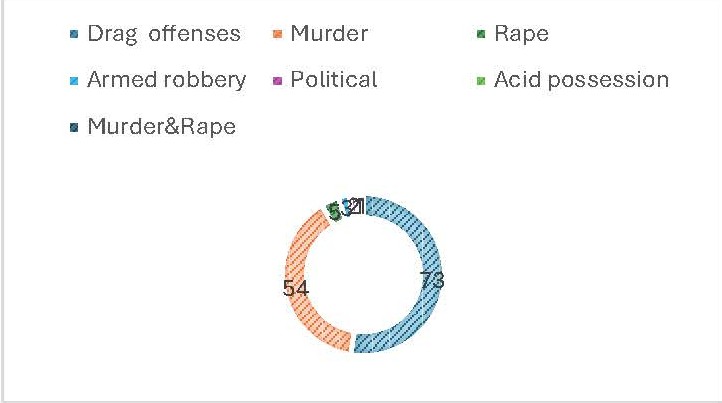

Among the 139 recorded executions in Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025), there was a wide range of criminal charges that led to the death penalty.

Data shows that over 52% of all executions (73 cases) were related to drug offenses. This high proportion once again reflects the ongoing use of harsh penal policies by the Islamic Republic in dealing with drug-related crimes—despite repeated criticisms from human rights organizations that these trials fail to meet international standards of due process, and calls for the reform of Iran’s drug laws.

In second place is the charge of murder, with 54 cases (approximately 39%). Although some of these sentences were carried out based on private complaints filed by victims’ families and implemented under the Islamic principle of qisas (retributive justice), many of these cases have faced serious criticism due to lack of due process, ineffective legal representation, and forced confessions.

A number of executions were also carried out for sexual offenses, which typically generate strong public reaction. However, case reviews show that trials for such charges are often conducted in Revolutionary Courts, rushed, and lacking the elements of a fair and comprehensive judicial process.

Additionally, two political executions were reported during this month:

- Rostam Zeinoddini

- Mohsen Langarneshin.

Given the vague nature of the charges and lack of transparency in the judicial proceedings, these cases are widely viewed as examples of the death penalty being used as a tool of political repression.

There were also less common cases this month:

- One person was executed for acid possession,

- Three individuals were executed for armed robbery.

While these offenses are serious, they did not involve loss of life, yet the Iranian judicial system continues to impose the death penalty for non-lethal crimes, raising significant human rights concerns.

Case Profile: The Execution of Saghar – Murder, Forced Marriage, and Gender Discrimination

On 12 Ordibehesht 1404 (1 May 2025), a woman named Saghar was executed in Ghezel Hesar Prison, located in Alborz Province, on charges of premeditated murder of her husband. Her last name was not mentioned in public reports. This case is one of the few documented executions of women in Iran during this year.

Saghar was accused of killing her husband Farid, six years earlier in Kamālshahr, Karaj, in collaboration with a man named Mehrdad. In the same case, Mehrdad avoided the death penalty by paying 300 million tomans in blood money (diyeh) and securing the consent of the victim’s family. Saghar, however, despite her claims of being in a forced marriage, enduring domestic abuse, and suffering from psychological distress, was executed.

This case highlights multiple layers of systemic discrimination against women in the Iranian judiciary:

- Forced marriage and domestic violence, which were critical contributing factors to the crime, were ignored during the legal proceedings.

- Mehrdad, the male co-defendant, was spared execution by paying financial compensation, while Saghar, the woman, had no such option and was ultimately hanged.

- The disparity in sentencing and outcomes between the male and female defendants underscores the deep flaws in gender justice within the legal system.

Saghar’s execution is not only another example of capital punishment being implemented, but also a striking case of social and gender injustice that deserves prominent attention in human rights reporting.

4. Marital Status and Family Impact

According to the data collected, among the 139 individuals executed in Ordibehesht 1404 (21 April – 21 May 2025), the marital status of only 20 individuals was confirmed—and all 20 were married. Given the lack of information regarding the rest, it can be inferred that the marital status of over 85% of those executed remains unknown.

These 20 married individuals were known to have had a combined total of 71 children, averaging approximately 3.5 children per person. While the age and gender of these children is not known, it is clear that the execution of their parents has left at least 71 children facing the trauma of parental loss, psychological distress, family instability, and social insecurity.

This data reflects only a fraction of the broader social consequences of capital punishment in Iran. The harm caused by executions extends far beyond the individual put to death—it devastates families, and children are often the hidden victims of this punishment.

In Iran’s legal system, the social and familial impact of the death penalty is largely overlooked. In contrast, many modern legal systems require supportive institutions to assess and assist the families—particularly children—of those facing severe sentences. Such mechanisms are either non-existent or severely dysfunctional in Iran.

5. Conclusion

The trend of executions in Iran during Ordibehesht 1404 has shown not only a significant quantitative increase, but also deep qualitative concerns, including the escalation of repression, systemic injustice, violations of minority rights, neglect of social and psychological circumstances, and disregard for Iran’s international obligations.

The compilation and publication of this report is an effort to document, preserve, and amplify the voices of the victims—with the hope that the path of justice, rehabilitation, and human dignity will one day replace the noose of execution in Iran’s legal system.