In the first quarter of 1403 (March 2024 – June 2024), Iran witnessed a significant number of executions across the country, drawing widespread attention. This report provides a detailed examination and statistical analysis of the executions that took place in the months of Farvardin, Ordibehesht, and Khordad of 1403. The main objective of this report is to offer a clear picture of the state of executions in Iran, examine the types of related crimes, and analyze the social and human rights impacts of these actions.

During this period, there was a notable increase in the implementation of death sentences, especially those related to drug offenses and murder. Additionally, the geographical distribution of executions across different provinces shows that certain provinces accounted for the highest number of executions.

This report aims to analyze and describe these events accurately using credible sources and available information. Besides statistical analysis, the social and psychological impacts of these executions on the victims’ families and the community are also examined.

Ultimately, this report is prepared with the aim of raising awareness within the international and domestic communities, creating grounds for increased pressure on the Iranian government to comply with human rights and international laws. We hope this report can play an effective role in promoting legal and human standards in Iran.

Report Content

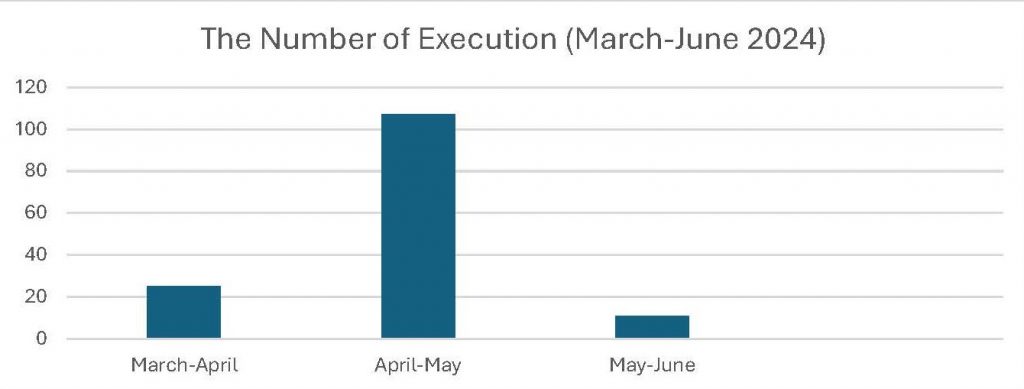

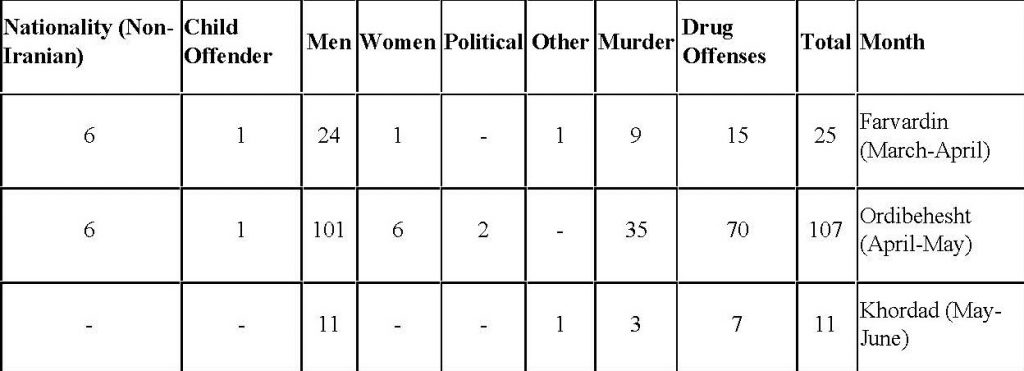

In total, 143 executions were recorded in Iran during the first quarter of 1403 (March 2024 – June 2024). These executions are broken down by month as follows: Farvardin (March-April): 25 executions, Ordibehesht (April-May): 107 executions, and Khordad (May-June): 11 executions.

It should be noted that many executions are not reported by domestic media and the judiciary. This is due to informational restrictions, censorship, and political and social pressures on media and human rights activists. This report only addresses available and accessible data, and it is likely that the actual number of executions is higher than the reported figures.

It appears that the highest number of executions was reported in Ordibehesht with 107 cases. This month had the highest number of executions by a significant margin compared to the other months in this period. The number of executions in Farvardin and Khordad was significantly lower than in Ordibehesht. This decrease can be attributed to various factors. For instance, Farvardin 1403 coincided with the month of Ramadan, during which, due to religious and spiritual beliefs, executions typically decreased. Additionally, following the helicopter crash that killed Ebrahim Raisi and the subsequent early presidential elections, the government’s and judiciary’s focus shifted to electoral issues and efforts to reduce social tensions, temporarily lowering the number of executions.

A comparative analysis shows that in the spring of 1403, the number of executions increased by approximately 36.19% compared to the same period last year (105 executions in the spring of 1402). This increase indicates an intensification of judicial policies in dealing with crimes, especially those related to drug offenses.

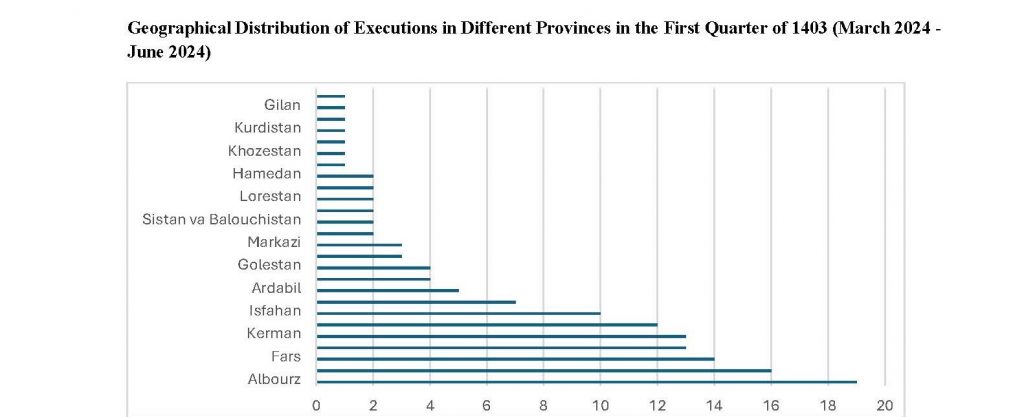

Geographical Distribution of Executions

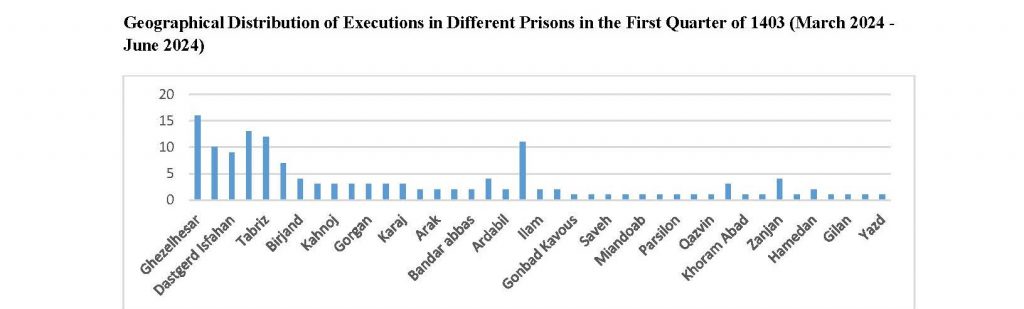

Executions in the first quarter of 1403 (March 2024 – June 2024) took place in 26 provinces and 41 prisons across the country. Among these, the provinces of Albourz, Khorasan Razavi, and Fars had the highest number of executions, with 19, 16, and 14 cases respectively. These regions were followed by Kerman, West Azerbaijan, and East Azerbaijan, which also reported significant numbers of executions. This distribution indicates a notable concentration of executions in specific provinces, suggesting variations in local judicial practices and crime rates.

This geographical distribution indicates that certain provinces had a higher number of executions compared to other areas. This disparity can be influenced by various factors, including judicial conditions, local crimes, and regional policies.

According to published reports, Ghezel Hesar Prison and Adelabad Prison in Shiraz reported the highest number of executions during the first quarter of 1403, with 16 and 13 executions respectively. This highlights the significant role these prisons play in the implementation of the death penalty within their regions.

Demographic Analysis of Executed Individuals

Reports indicate that the age range of those executed was between 19 and 53 years old, although the ages of a significant number of the victims were not reported. Among the executed, seven were women, and two were minors at the time of their crimes.

“Marjan Hajizadeh,” who was arrested at the age of sixteen for drug-related offenses, was hanged on 23 Farvardin 1403 (April 11, 2024) in Zanjan Prison at the age of nineteen. Additionally, “Ramin Saadat Zamani,” who was accused of murder during a street fight at the age of seventeen, repeatedly professed his innocence but was executed in Miandoab Prison on 29 Ordibehesht (May 18, 2024) at the age of twenty-two.

Furthermore, “Rashid Baluchi,” a mentally ill individual with a medical red card, was executed on 9 Ordibehesht (April 28, 2024) for murder in Bandar Abbas Prison.

Several of the executed individuals during this period were non-Iranian nationals, specifically Afghans. Twelve of the executions in the first quarter of 1403, accounting for about 11% of the total, involved Afghan nationals.

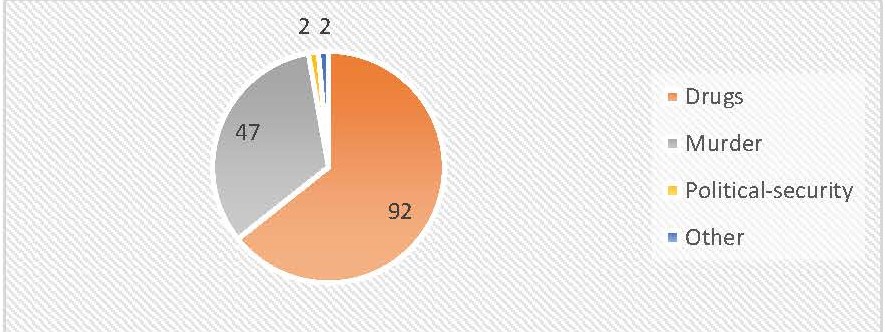

Reasons for Executions

The data indicate that the executions were carried out for various reasons, including drug-related offenses, murder, political and security crimes, and other crimes such as rape. The breakdown of these reasons highlights the diverse nature of the crimes leading to the death penalty in the first quarter of 1403.

The data indicate that the majority of the executions, 64%, were for drug-related offenses. Following this, 33% were executed for murder, including those sentenced to Qisas (retributive justice). One concerning aspect of Qisas is the collective execution of individuals involved in a shared crime. For instance, on 23 Ordibehesht (May 12, 2024), a group execution was carried out for individuals involved in the collective murder of a person during a street fight. In this case, six people were sentenced to death, and five were executed. The sixth individual, Qasem Salehi, escaped execution by paying blood money (Diya) amounting to 5 billion tomans to gain the consent of the victim’s family.

This incident highlights the Iranian judicial system’s practice of collectively sentencing individuals involved in a single crime to death, regardless of each individual’s role and level of involvement. Additionally, the issue of paying Diya and the different outcomes for defendants underscores deeper issues such as economic justice and financial discrimination, suggesting that individuals with better financial resources can secure more favorable judicial outcomes.

Impact of Executions on Victims’ Families

Based on the details published about the victims of executions during this period, a portion of the information pertains to victims who were married and had children. According to the reports, during the first quarter of 1403 (March 2024 – June 2024), 55 children lost at least one parent due to executions.

Losing at least one parent to execution during childhood can have profound and lasting effects on the children’s psyche. These impacts may include anxiety, depression, behavioral issues, and persistent fears, potentially leading the children to face similar fates as their parents. For example, Fariborz Dadgar, executed on 30 Ordibehesht (May 19, 2024) in Sepidar Prison in Ahvaz for drug-related offenses, met the same fate as his father, who was executed in the same prison in 2008 on similar charges.

Many families that lose their breadwinner due to executions face severe economic challenges. These challenges may include reduced family income, increased living expenses, and general hardship. The lack of adequate economic support from the government and charitable organizations often leads these families into poverty and homelessness. Additionally, many of these families and their children face the risk of discrimination and stigma in Iranian society, exacerbating their psychological and social problems. The children from these families might encounter discrimination and social isolation at school and in their communities, which can have detrimental effects on their personal growth and development.