Seyyed Ebrahim Raisi al-Sadati, born in 1960 in the Noghan neighborhood of Mashhad, and the eighth president of Iran, was killed in a helicopter crash on May 20, 2024, at the age of 64. His death, although celebrated as good news on social media with satire and jokes by users, and with dancing and joy among the people of Iran, further increased disgust and surprise at the performance of the Security Council regarding a minute of silence in respect for his death and the condolences expressed by the U.S. Department of State.

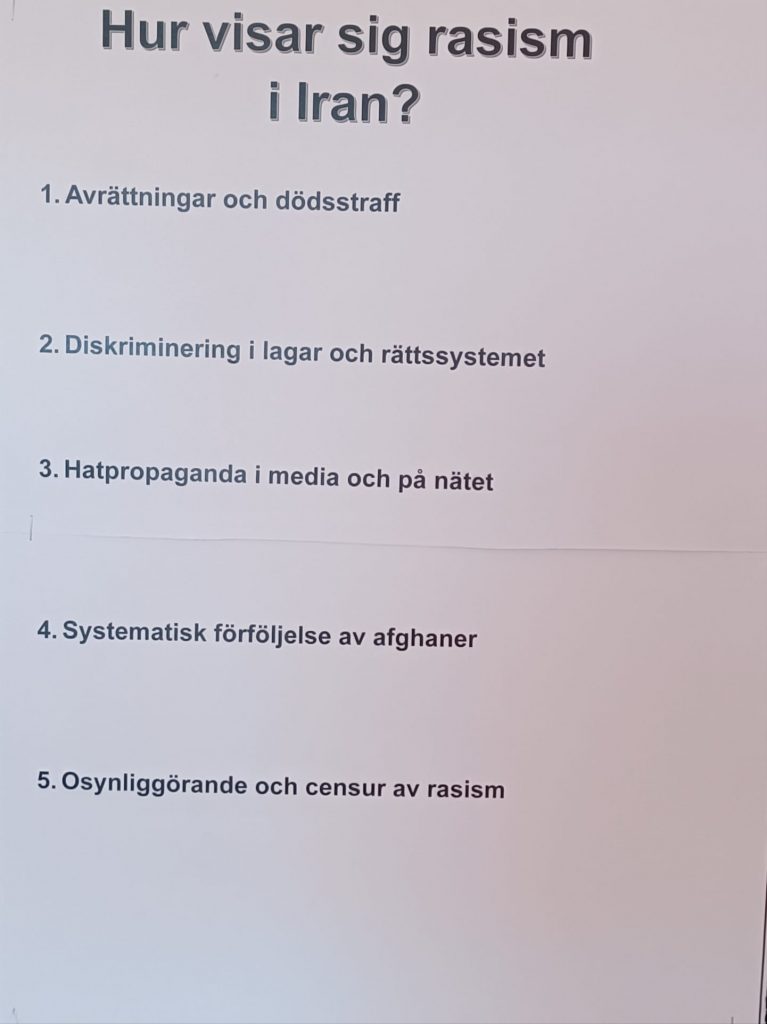

Although Raisi’s name is tied to the mass slaughter of political prisoners in 1988 and human rights organizations along with the victims’ families demanded his trial, the reality is that during his years of activity in the judicial and political system of the Islamic Republic, his victims were not only political prisoners but also other criminals and the general populace.

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Raisi quickly assumed various responsibilities within Iran’s judicial system. Starting as a judicial assistant in Karaj at only 20 years old in 1979, he was soon appointed as the prosecutor of Karaj, and during the summer of 1982, he simultaneously took on the role of prosecutor for the city of Hamedan. Later, he was introduced as the prosecutor for Hamedan province and held this position from 1982 to 1983. During the years he served as prosecutor of Karaj, the people of Karaj vividly remember the frequent floggings of criminals, particularly women, and the public stoning of a man in the Ferdows township.

The harassment and execution of Baha’is in these two cities are also recorded in Ebrahim Raisi’s dark résumé. In this regard, one can refer to the case of Mrs. Eshraqiye Foruhar and her husband Mahmoud Foruhar, who were arrested in 1981 and executed in Karaj prison the following year. Several political prisoners and government opponents were executed during his tenure as both judicial assistant and prosecutor in the prisons of Karaj and Hamedan. Examples of political prisoners executed during his term as prosecutor include 22-year-old Gholamreza Akhlaghi, 25-year-old Zohreh Shakari, 26-year-old Ardeshir Kargar, and 21-year-old Mohammad Shafaat.

In 1985, during the presidency of Mousavi Ardebili, Raisi was appointed as the deputy prosecutor of the Tehran Revolution, a position he held until 1989. He played a key role in the executions of political prisoners in 1988 as a member of the “death committee.” In 1989, Raisi was appointed by Yazdi as the prosecutor of Tehran and held this responsibility for five years until 1993. During these years, the news of amputations of thieves’ fingers in Tehran and other provinces became increasingly newsworthy. Additionally, the flogging of young men and women intensified due to what the judiciary identified as relationships outside of marriage.

During the presidency of Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi over the judiciary, Raisi was chosen as the first deputy of the judiciary in 2004 and served in this position for 10 years, five of which were under the presidency of Sadegh Amoli Larijani. Throughout this 10-year period, we witnessed suspicious deaths of prisoners during detention, widespread executions, and amputations. He was one of the factors in suppressing the Green Movement and was one of the officials handling complaints about sexual assault on prisoners, which in a report to the head of the judiciary, he declared the claims of sexual assault on prisoners to be baseless. He also described the protests related to the Kahrizak case on February 21, 2010, as a grave and unforgivable sin, minimizing the Kahrizak atrocities as “misdemeanors that occurred in dealing with this injustice.”

Raisi became the head of the judiciary in February 2019, with a human rights record far heavier than his predecessors, openly supporting punishments such as execution, stoning, and amputation of criminals, which he considered among his greatest honors. The tragic plane crash of the Ukrainian airline in 2020 during his tenure as head of the judiciary, which he referred to as a “regrettable accident,” and the theatrical court proceedings of this tragedy, incited the anger of the Iranian people and the victims’ families.

In 2021, he was “appointed” as the president of Iran. Following the killing of Mahsa Amini by the morality police, the “Woman, Life, Freedom” revolution ignited in 2022, leading to deaths, imprisonments, disfigurements, and executions of protesters. Under his government, the bill on hijab and chastity was passed, aimed at increasing systematic gender discrimination and suppression of women. Many professors, artists, and students were expelled from work and study, and pressure on media professionals significantly increased.

While Raisi’s crimes are no less than those of Hitler and Mussolini, and he should be considered the father of the Taliban’s judicial practices, the human rights situation in Iran is one of the most painful and disastrous, registered internationally as one of the worst types of dictatorial governance. The unsightly actions and sympathetic words from an international body like the Security Council not only represent a contradiction in the United Nations’ declared democratic and human rights values but also an outright insult to the rights and lives of countless people victimized by Raisi and his counterparts. This unconventional move by the Security Council not only indirectly endorses repressive behaviors but also sends a dangerous message to other autocratic regimes that yes, human rights can be overlooked for transient and strategic interests. Ultimately, it must be said that the Security Council and governments whose sympathies boil over for the death of a criminal are accomplices in the crimes of regimes like Iran.